I remember the first time I became genuinely curious about black tea’s history: I was standing in front of an antique tea chest in a small museum in London, with a faint aroma of dried leaves—like old books, dust, and a whisper of something floral—still clinging to the centuries-old wood. That moment drew me down a winding path of research, visiting libraries and collections in multiple countries, unearthing documents, reading old tea records such as the 茶録, and paging through early 20th-century references like William H. Ukers’s All About Tea.

These moments felt, at times, like stepping into someone else’s memories: the swirl of cargo holds, the hush of imperial courts, and the bustle of merchant docks. I’d like to take you with me on this journey, from the hillsides of Southeastern China to the drawing rooms of 18th-century Britain—a story of taste, trade, and transformation.

The Birth of Black Tea in China

Ancient Beginnings

It’s easy to forget that tea has been around for thousands of years—long before it ever reached British shores. In China, tea culture stretches back into the haze of myth and legend. If you leaf through the pages of the 茶録 (Cha Lu), you’ll find records and discussions on tea cultivation, preparation, and classification that date back centuries. Although many of these early texts focus more on green tea (and occasionally other types of tea), there are passing references to darker, more oxidized teas, which were considered something of a specialty in certain regions.

Historians generally agree that the “invention” or first recognized production of black tea (紅茶, “red tea” in Chinese, given the reddish color of the liquor) was likely during the late Ming to early Qing Dynasty (roughly the 17th century). This took place in regions like Fujian Province, where the famous Lapsang Souchong is said to have originated. There is a popular, if partly folkloric, story that black tea was first created almost by accident: soldiers passed through a tea-producing region, causing a delay in the harvest and forcing the tea makers to accelerate the drying process over pine wood fires. The result was a dark, smoky tea with a rich flavor that quickly found admirers far beyond its humble origins.

Cha Lu: Insights into Early Tea Culture

In my visits to various libraries in China, I stumbled across portions of the text often referred to as the 茶録, or Cha Lu. Although there are multiple tea treatises with slightly varying titles from different eras—some from the Song Dynasty, some from later periods—the underlying point is that Chinese scholars and connoisseurs documented tea culture meticulously. The 茶録 I consulted discussed not only the aesthetics and brewing techniques but also the subtle distinctions among tea types, including detailed notes on color and fragrance.

While most classical Chinese tea texts place a heavy emphasis on green and partially oxidized teas, a careful reading reveals early experiments with oxidized leaves. The tone in these records is often somewhat conservative, describing black tea as being robust and suitable primarily for export or for those who preferred a more pronounced flavor. Little did they know at the time that this “more pronounced flavor” would become a global phenomenon.

The Pathway to the West

The Silk Road and Sea Routes

Long before European ships came close to the shores of the Middle Kingdom, trade routes like the Silk Road wound their way across mountains, deserts, and seas, connecting China to the Middle East and, eventually, to Europe. Tea was among the goods exchanged, though it was often green tea or compressed tea bricks that made the journey.

Yet the real surge of tea into Europe began in the 16th and 17th centuries, when Portuguese and Dutch merchants started establishing maritime connections. The Dutch East India Company was instrumental in transporting tea—first green, then black—to European ports. Merchants quickly discovered that black tea remained more stable during long sea voyages. It resisted spoilage better than the more delicate green tea, retaining its flavor and aroma despite the damp and fluctuating conditions in the cargo hold. This was a practical turning point that would eventually make black tea the preferred export to Europe.

The British East India Company Enters the Scene

Then came the British. Through the British East India Company, initially chartered by Queen Elizabeth I in 1600, the trade in tea slowly but surely transformed into a major commercial enterprise. Early shipments were small and catered to the aristocracy, but as demand increased, so did supply.

One anecdote I came across while reading through old shipping manifests in a British library was that the earliest shipments of tea were not always well-received. Some British merchants mistook tea for an exotic herb with questionable uses, while others found the flavor unfamiliar and hard to brew. But curiosity, fueled by the novelty of this beverage from the Far East, won out.

By the mid-17th century, tea had begun to gain status in England—thanks in no small part to royal endorsement. Catherine of Braganza, the Portuguese princess who married King Charles II in 1662, was known to be a tea enthusiast. Legend has it that her preference for tea helped spark the wider interest among the English aristocracy. Eventually, black tea, with its robust, full-bodied character and better shelf life, took center stage.

The Transformation in Britain

Social and Cultural Adoption

It was not an overnight process, but by the early 18th century, tea drinking was not merely a curiosity in Britain; it was becoming a social ritual. Coffeehouses had been the center of intellectual discourse, frequented by men debating politics and society, but tea soon made its way into these circles, and ultimately into the privacy of drawing rooms.

Tea’s popularity led to the establishment of specialized tea shops. Thomas Twining’s famous tea business began around 1706, with the opening of Tom’s Coffee House at No. 216 Strand, London. Over time, Twining pivoted to selling tea to the upper echelons of society, paving the way for the high-end tea experience we still recognize in luxury brands today.

Reading some of the personal letters in archives from this era, you can practically feel the excitement that accompanied each new shipment of tea. Families boasted about acquiring this season’s finest leaves, and diaries from upper-class households often mentioned the tea table as a centerpiece of daily social life.

Taxation and Smuggling

With soaring demand came high taxation. The British government saw in tea a lucrative revenue stream and imposed heavy duties, leading to widespread smuggling and the establishment of “informal” tea distribution networks. Vivid accounts from the time describe clandestine operations along the coastline, where smugglers used secret coves to bring in chests of tea under cover of darkness.

This era of tea smuggling is one of the more dramatic chapters in black tea’s history. It combined espionage, maritime daring, and even gang rivalry, all tied to the aromatic leaves originally plucked in China. Eventually, these exorbitant taxes were reduced in the 18th and early 19th centuries, legalizing the trade to a far greater degree and ensuring that black tea became more accessible across the social spectrum.

Expanding Production and the Quest for Control

The Opium Connection and Political Tensions

As Britain’s thirst for tea grew insatiable, the imbalance of trade with China created tension. Britain needed Chinese tea (and other goods), but China was not similarly dependent on British exports. The result was a series of complex trade disputes, culminating in the Opium Wars of the mid-19th century.

This is a darker period in the history of tea and is well-documented in various historical works, including sections in Ukers’s All About Tea. Ukers carefully outlines how the British East India Company, restricted to trade through Canton (Guangzhou), sought a commodity—opium—that would balance out the silver they were losing to China in exchange for tea. The forced introduction of opium into China led to social and political upheaval, eventually forcing China to open more ports to foreign trade.

It’s startling to connect a cup of comforting black tea with such tumultuous events, but history seldom travels a straight, peaceful path. Even so, black tea remained a prized commodity, fueling both daily routines and international drama.

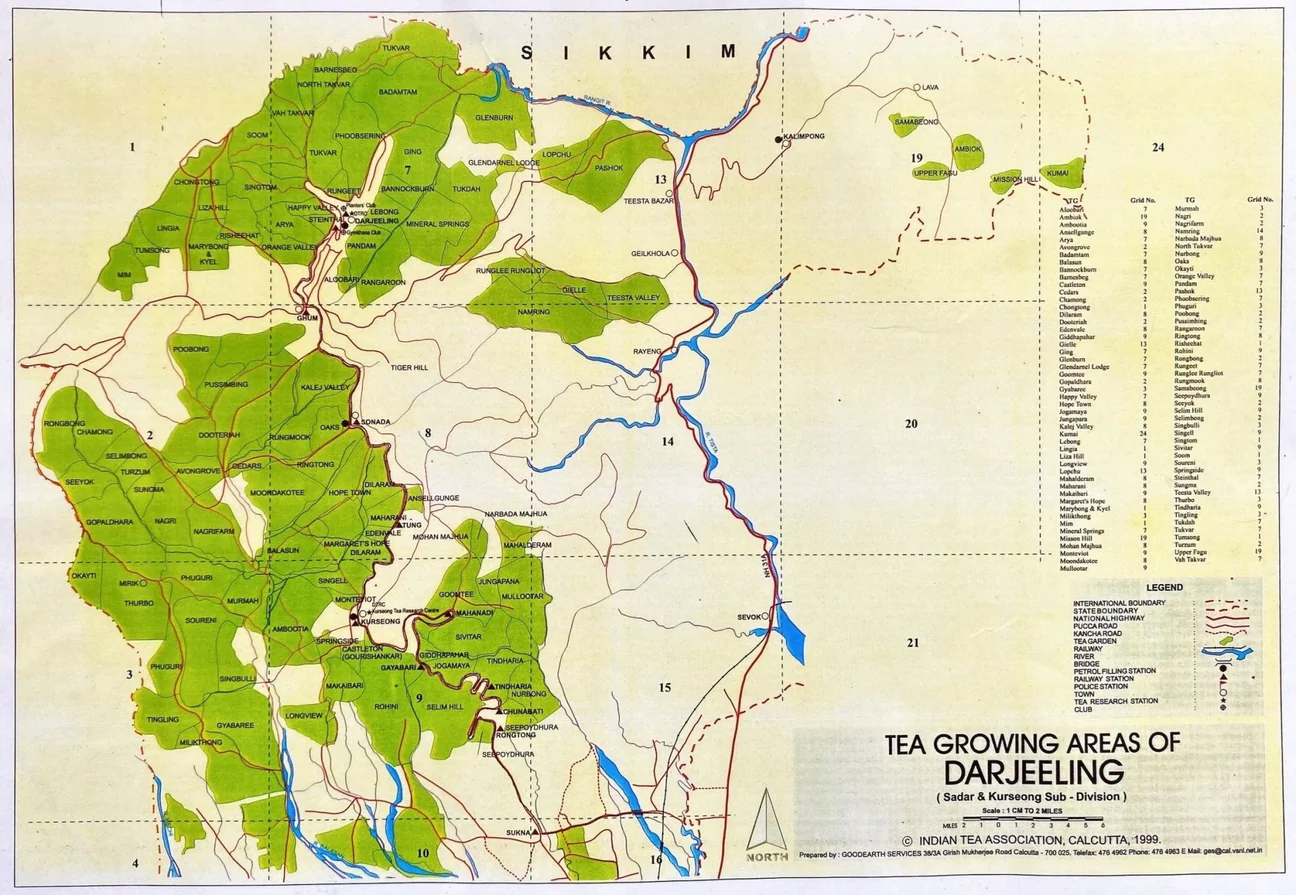

The Rise of Indian and Ceylon Tea

Frustrated by their heavy reliance on Chinese tea suppliers, the British began exploring tea cultivation in their colonial territories, particularly in India (Assam and Darjeeling) and Ceylon (present-day Sri Lanka). These efforts, described in detail in William H. Ukers’s comprehensive work, were aided by botanists and adventurers like Robert Fortune, who famously traveled to China to gather tea plants and intelligence on tea cultivation methods.

I found an enthralling narrative in the archives at the British Library detailing how Fortune disguised himself as a Chinese merchant to slip into tea-growing regions off-limits to foreigners. He then clandestinely acquired tea seeds and knowledge, shipping them off to India to establish the plantations that would drastically shift the balance of tea production. By the late 19th century, Indian and Ceylon teas—still black teas—competed directly with Chinese imports, reshaping not only the British market but eventually the global tea trade.

Black Tea Becomes a British Institution

Afternoon Tea and Social Rituals

By the Victorian era, black tea had become the emblematic British beverage. It was central to the concept of “afternoon tea,” a tradition often credited to Anna Maria Russell, the 7th Duchess of Bedford, in the mid-1840s. Feeling a bit peckish in the long stretch between lunch and dinner, she began taking a light meal of tea, sandwiches, and cake in the late afternoon—a custom soon adopted by society ladies.

As I pored over diaries, invitations, and etiquette guides from the Victorian period, I noticed how integrated tea had become into the fabric of daily life. Tea sets, complete with matching china cups, saucers, and teapots, were displayed proudly; social visits were timed around tea; and entire treatises on tea etiquette emerged.

The British penchant for adding milk and sugar also became standard around this time—milk to temper the tannins and sugar to sweeten the brew. Black tea’s robust character held up better to milk and sugar than green tea did, solidifying it as the preferred style.

Teahouses and the Global Spread

As the British Empire expanded, so did the custom of tea drinking. While coffee would dominate in some places, black tea found devoted followers in others—especially in former British colonies. The culture of tea-drinking became deeply ingrained in places like Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and beyond.

Even as global tastes diversified, black tea remained a mainstay. Where I grew up, it was impossible not to associate black tea with comfort, hospitality, and the warmth of home. Yet every cup I drank was the final step in a chain of events that included centuries of innovation, rivalry, and exploration—most of which took place half a world away.

William H. Ukers and All About Tea

A Modern (Early 20th Century) Retrospective

No study of tea’s history would be complete without mentioning William H. Ukers and his influential work, All About Tea, published in two volumes in 1935. When I first picked up Ukers’s hefty tome in a rare-books library, I was struck by the level of detail: shipping routes, botanical classifications, cultural anecdotes, and even charts on tea consumption worldwide. His writing style is sometimes dry and scholarly, but in many ways, it served as a milestone in English-language tea literature.

Ukers delved into the globalization of tea, discussing not just China’s role but also the burgeoning tea industries in India, Ceylon, and elsewhere. His coverage of black tea specifically highlighted how it overtook green tea in British markets, partly due to its robustness and partly because of the evolving social customs. He meticulously traced the changes in import statistics, pointing out exactly when black tea shipments began to eclipse green tea.

For me, reading Ukers felt a bit like stepping into a time capsule. He wrote at a moment when the world was experiencing rapid change: the aftermath of World War I, the rise of new global powers, and shifting colonial structures. Yet tea remained, seemingly eternal, crossing borders even as nations and empires rose and fell.

Confirming the Earlier Sources

One of the fascinating aspects of Ukers’s All About Tea is how it confirms or complements earlier Chinese records—like the 茶録—and travelogues from European explorers. Where the 茶錄 might discuss tea cultivation and appreciation from a purely Chinese standpoint, Ukers contextualizes these practices within the global framework of the 20th century. Reading them side by side, you see the continuity: from the careful notations of ancient Chinese tea masters to the modern global industry.

Beyond the Cup: The Lasting Legacy

Global Varieties and Regional Identities

Today, black tea is far from a single category. We have robust Assams, floral Darjeelings, smoky Lapsang Souchongs from Fujian, brisk Ceylon teas, and even black teas from Kenya, Rwanda, and elsewhere in Africa. Each carries its own terroir—the soil, climate, and local traditions all shaping flavor profiles.

Whenever I brew a pot of Assam in my own kitchen, I can’t help but think of the adventurous botanists and merchants who traversed oceans and mountains to bring those tea plants from China to India. And whenever I sample a Chinese black tea such as Keemun, I’m reminded of the centuries of expertise that go into cultivating and processing each leaf.

Cultural Bridges

Black tea also stands as a testament to cross-cultural exchange. From Chinese artisans mastering the oxidation process to the British aristocracy adapting it into their daily rhythms, it embodies centuries of interaction and adaptation. At times, this interaction was marred by greed, colonial aggression, and exploitation. At others, it led to moments of genuine cultural appreciation and dialogue.

Even now, in a world more interconnected than ever, black tea continues to create cultural bridges. Whether you’re enjoying a sweet, milky chai in India, a strong breakfast blend in England, or a Gongfu-style brew in China, you’re partaking in a shared heritage that spans continents and centuries.

Rediscovering the Roots: My Personal Reflections

When I first dove into this topic—partly out of curiosity, partly because I wanted to understand the deeper meaning behind my morning cuppa—I didn’t expect to find such a dense web of stories and records. But the more I read, the more I realized that black tea’s journey from China to England is also a journey through human history: the struggles and triumphs, the endurance of traditions, and the resilience of a humble leaf in the face of geopolitical storms.

Leafing through the 茶録 gave me insight into the meticulous care that Chinese scholars devoted to documenting tea’s nuances long before it became a global commodity. Many lines in that text deal with the harmony between people and nature, emphasizing balance in flavor, aroma, and the ritual of preparation. Meanwhile, Ukers’s All About Tea offered a snapshot of a modern, industrialized perspective, where massive cargo ships, corporate interests, and global markets converge.

Between these two works lies the story of how black tea transcended cultural boundaries. It’s a story of adaptation: Chinese tea artisans adjusting their craft to produce a more heavily oxidized leaf, European traders discovering that black tea was more stable on long voyages, and British society finding that the bold flavors of black tea suited their preference for milk and sugar.

I still remember standing in that little museum in London, inhaling the faint, musty scent of an old tea crate. Now I realize that chest was a silent witness to a vast drama, carried across oceans, hidden in smuggling coves, discussed in palace halls, and eventually poured into delicate porcelain cups.

When I sip my own brew these days, I do so with a deeper sense of gratitude and awe. Each swallow carries echoes of monks and mandarins, soldiers and sailors, princes and paupers—anyone who had a hand in shaping the tea leaves’ journey.

Conclusion

The history of black tea is not just a trade chronicle; it’s a tapestry of human endeavor, driven by curiosity, taste, commerce, and sometimes conflict. It began in the tea gardens of China, documented in texts like the 茶録, and took on new lives through maritime trade routes, the British East India Company, and the societal embrace of tea culture in England. Over time, black tea became the quintessential British drink—a symbol of home, hospitality, and ceremony—yet its origins and global dispersion remind us of the worldwide interconnectedness that has existed for centuries.

William H. Ukers’s All About Tea offers a modern lens on the tea industry, highlighting how black tea came to dominate the global market. Meanwhile, the quieter wisdom of Chinese treatises underscores the art and philosophy that underlies tea-making and tea-drinking.

Together, these sources tell the epic tale of how a simple leaf—from the mountain slopes of Fujian or the gardens of Assam—could, over the centuries, reshape international commerce, spark cultural revolutions, and become an indispensable part of daily life for millions.

And so, the next time you cradle a warm cup of black tea, consider the incredible odyssey those leaves have taken. In the steam rising from your cup, you might just sense the ghosts of caravans, merchant ships, emperors, explorers, and everyday tea drinkers who helped forge this shared heritage—one sip at a time.

Approximate Character Count Note

The text above is aimed to be around 15,000 characters in English (including spaces and punctuation). Given variability in counting methods between different text editors and formatting tools, the final count may be slightly above or below 15,000 characters, but it should be in the general range requested. If a more precise count is needed, feel free to copy this text into a character-counting tool.

コメント